I went with this group of people as they trekked to the Black Creek Trailhead which leads some 30 miles to Waldo Lake. We helped set up a wilderness information trailhead sign that had been knocked over and broken by a falling tree. It was a 100 degree day and it felt like it was 90 degrees while we were digging the hole for the sign, even in the shade of the forest. If you’ve hiked on a Forest Service Trail and you were able to safely get over fallen branches or mud slicks, you have these people, and especially the volunteer coordinator Judy Mitchell, to thank. This was published in Boomer and Senior News in September 2014.

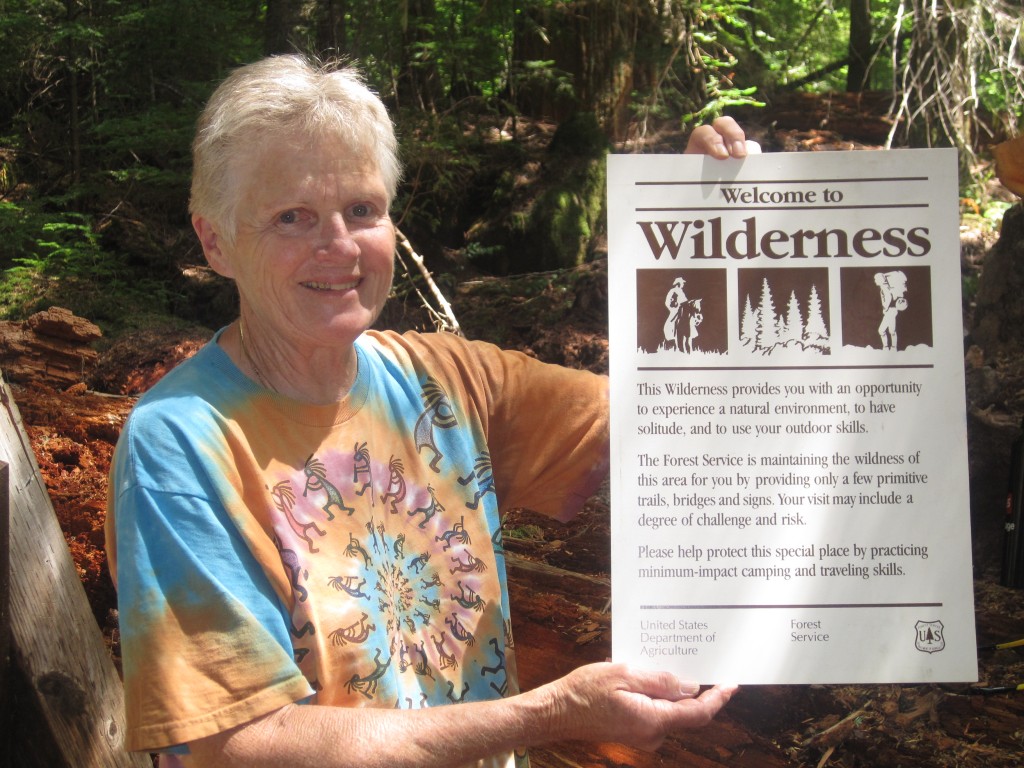

Judy walked farther along the trail to observe the damaged sign that had been placed there previously. Her dog, Monte, followed along to supervise. Photo by Vanessa Salvia

Out in the Backcountry

Volunteers trail maintenance crews keep trails clear and campsites clean.

By Vanessa Salvia

It’s nice to imagine that a hiking trail, once cleared, stays cleared. But in fact, publicly accessible hiking trails in wilderness areas require regular, ongoing maintenance in order to stay usable. Trees and branches fall onto paths. Rain erodes walkways. Bridges need strengthening. Trail markers and other signage needs to be placed or re-placed.

It’s also nice to imagine that the United States Forest Service has a well-paid crew to take care of these repairs, but again, that’s not the case. Most of these behind-the-scenes repairs are handled by a small but dedicated group of volunteers.

Judy Mitchell coordinates much of this volunteer work. She’s a fit, young-looking 73-year-old who retired from a forest service wilderness crew in 2005. “I started the volunteer program to help keep the people active that were already helping out,” she says. “It started organizing slowly.”

One of the things that was always needed was volunteer training. The Forest Service crew found it difficult to do this because they had their own jobs that needed to be done, so Mitchell stepped in to start a training program. “It’s now grown into a three-day training program that takes place in May,” Mitchell says. “It’s free to anyone who wants to volunteer. We have had anywhere from 90 to 140 people come for those three days.”

Mitchell’s career with the Forest Service itself was born from volunteer work. “I always liked the outdoors and when I moved here from Colorado I put my name in as a volunteer,” she says. “I volunteered for one year and then they asked me if I wanted to be hired as a seasonal worker.”

At that time, in 1987, the Waldo Lake Wilderness had just been designated three years earlier. The Three Sisters and Diamond Peak wilderness areas were enlarged, and the Forest Service had few people to go out there. The Waldo Lake Wilderness area used to be a popular place for motorcycle parties, Mitchell recalls, so it needed a lot of cleaning up.

Mitchell had worked for the Catholic Church for about 25 years, and when the Forest Service offered her a seasonal job, she felt it was time to take it. She joined a wilderness crew for the Middle Fork Ranger District of the Willamette National Forest, a large area that encompasses more than 750,000 acres.

“My job was to go out during the summer from May to October, even holidays,” says Mitchell. “I went out four days a week to clear trails, pick up trash and clean wilderness camp sites. I spent all my time hiking.”

When Mitchell says she “went out,” that means she camped four days a week, by herself or with her dog, Monte. Other than the many nice people she met, Mitchell had some memorable encounters with wildlife while working. She saw a young bear near Box Canyon, and stopped her truck to watch it, keeping a safe distance. Rather than moving on his way, the bear came over to the driver’s side window of her truck, which was open, and stood up. “He put a paw on the outside mirror and the other on the window and leaned in and smelled me,” Mitchell says. “I could actually see up his nose holes! There was no fear between either of us. It walked along on its hind feet and checked out the back of the truck and finally lost interest and lumbered up the road to where it was going.”

At that point, Mitchell knew she had to do something. “I can’t let this bear think that humans are all cool, so I jumped up and made noises trying to scare it away,” she recalls. “What it did was lay on its back and put its leg up, so I had to chase it off. I really didn’t want to do that but I knew if I don’t it’s going to think that we’re all kind and we’re not. It looked at me like, ‘you’re no fun.’” After relating the experience to colleagues, Mitchell figured out that it was probably a young bear that had just gotten kicked out of the family by the mother after she had a new cub. “This guy didn’t know too much about the world yet,” she says. “It was an experience I’ll never forget.”

Mitchell had several back surgeries over time, but rather than giving up her work, she got a llama to carry her gear, and eventually got two llamas. One llama, Camas, is now a therapy llama. Mitchell takes him to memory care units and schools to teach kids about leave-no-trace camping. Mitchell also donates platelets every other Thursday, so she does not join the volunteer group on each trip.

The High Cascades Forest Volunteers (HCFV) don’t need to be prepared for four days of camping like she did. The volunteers go out for the day, or overnight if they wish to and it’s prearranged. Mitchell says that most of the volunteers she coordinates are in their 50, 60s or 70s, because they have the time. Often, the volunteers are avid hikers or equestrians who want the trails to be clear for others as they were clear for them. Several horse groups go out on weekends. “They would like the trails to be clear so they can ride their horses,” says Mitchell.

Volunteers meet each Thursday at the Middle Fork Ranger District just west of Oakridge on Highway 58. They drive to the worksite and usually spend the day or part of the day taking care of what needs to be done. “Our main job is to clear trails,” says Mitchell. “I tried to enlarge the program so that people can do many things. There is a lot of office work that needs to be done and sites along roads that need to be checked, but it’s developed into mostly clearing trails, walking trails and reporting to the Forest Service so that they can be cleared. It’s pretty important to know what’s on the trails so you don’t send a crew out there and there’s nothing there. We need to know the size of the tree, and the location and things like that.”

In late July, Mitchell and four volunteers, Rich and Jan Anselmo, Rhonda Levine, and Mike Kinyon, met at the Middle Fork station to assemble signage for trailheads. After gathering up the tools they needed to drill the holes for assembly of three signs, the group piled into a Forest Service van and drove several miles east of Oakridge and then 8 miles down a dirt road to the Black Creek trailhead in the Waldo Lake Wilderness to place one of the signs. It was slow-going, assembling the signs and then trying to dig through rocks for the post holes, so they placed only one sign that day rather than the three they were planning. But that’s sometimes how it goes…the Forest Service is a cash-strapped organization that can’t always supply the necessary items, and sometimes things don’t come together as smoothly as they should.

Husband and wife Rich, 64, and Jan, 62, are avid outdoor lovers who help because they like to give back. “This is the perfect volunteer job,” says Jan. “You get to go out in the woods helping to maintain the trails you love, and get a little exercise. Once you start volunteering you realize how much work there is to do.”

“And it’s fun!” says Rich, as he breaks a sweat digging postholes with a shovel. Rich was a meteorologist for the KMTR television station for 35 years. Now, he lives in Oakridge and manages a private weather consulting business. Though he’s under cover of trees, it’s still a 90-degree day. “Isn’t this fun?” he says, brandishing the shovel. He’s working hard, but the camaraderie is fun. And the effort is tempered by the knowledge that he is contributing something important. “Somebody did it for us, so that we could come out here and hike,” he says, “so it’s a way to keep it alive for the next group of people.”

Mike Kinyon is a member of a trail maintenance group called The Scorpions, part of the larger group of HCFV trail stewards. Kinyon is a crosscut saw sharpener, so when he goes out on the trails, it’s mostly with a saw in hand.

The annual training certifies volunteers to do trail work, including using a chainsaw and crosscut saw. The education also covers trail maintenance, trail design, trail reconstruction, managing a trail crew, wilderness first aid and CPR, and many others. The training is free of charge and volunteers may attend the full weekend or only portions of the training. To register for next year’s training, just let Judy Mitchell know you’re interested. “What’s neat about working with volunteers is that they want to do it,” she says. “You don’t have anybody complaining or moaning and groaning. If they can’t go out they wont go out.”

Potential volunteers don’t need to have any particular skills other than basic hiking ability. Checking trails for downed trees doesn’t take much, although there is a way to report observations that is more helpful than other ways, and that is one of the things the volunteers are taught to do.

“If nobody has that that training they can still help out and go out with somebody else,” says Mitchell. “Not everybody wants to clear trails because that’s hard work, but there are a lot of jobs that can be done. Most of the folks that volunteer say they want to do something in return for all the years they were out there and the trails were clear and the sites were clean.”

For more information and to register for the trainings, visit: http://www.highcascadesvolunteers.com/Training/SpringTraining.html

No comments yet.